A few years ago, I spent 6 months as a Chaplain Intern at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Clinical Center is a unique place — every patient there is participating in a research protocol. Often, they have either a very rare condition or a disease that has been resistant to treatments, and so they’ve made the voluntary (and courageous) decision to be a part of an experimental treatment with the hope that their participation will lead to a healthcare breakthrough. Some vital treatments have emerged from the research at NIH, including the use of lithium to treat bipolar depression, a breakthrough in mental healthcare to which I have a particular and personal relationship.

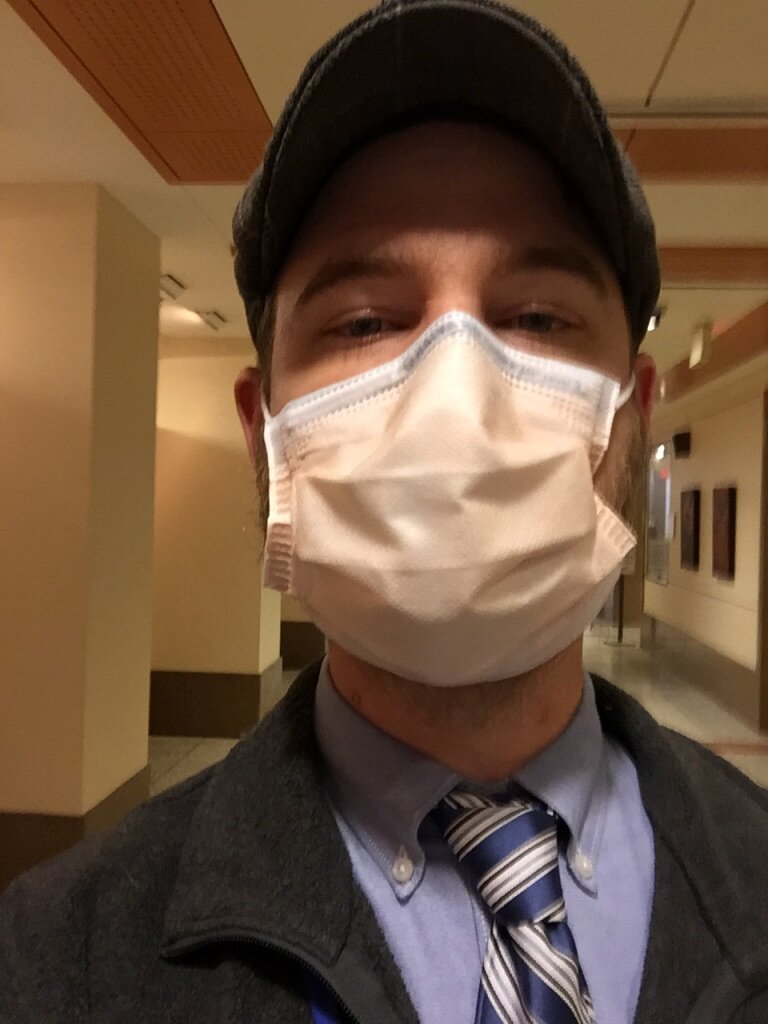

At the NIH Clinical Center, Winter 2018

Nobody at the Clinical Center is there for something “routine.” They are often far away from home, and our role as the Department of Spiritual Care was to be part of the holistic care NIH provides, visiting patients, lending a listening ear, giving people space to process their experiences, and seeing if they had particular religious needs that we could either provide directly or facilitate their connection and continuation.

One of the floors I was assigned at NIH was dedicated primarily to stem cell transplants. Folks getting stem cell transplants had to be in the hospital for a loooooong time — 100 days — while their immune systems basically rebooted completely, and while the doctors and nurses tried to keep their immune systems from rejecting the new stem cells. (Please understand as you read this that I’m trained in theology and spiritual care, not in medical research, so please forgive my inaccuracies in language here).

All of which meant that, in order to sit with folks, talk to them, and literally meet them where they were — often in rooms with closed doors marked with contact isolation signs — I had to adopt some practices that are not usually part of my pastoral care routine in my more ‘usual’ role as as a campus minister and college chaplain: hand washing and sanitizing before and after entering each room, donning a thin yellow gown and gloves, and, often, putting on a mask.

We masked up before going into rooms, not to protect ourselves — the patients I was visiting did not usually have any kind of contagious condition — but, of course, to protect the patients I was assigned to care for, whose immune systems were severely compromised by the experimental procedures in which they were participating. We wore masks to prevent us from passing germs to a patient, germs which might not have much of an impact on me but could have major health impacts on our immunocompromised guests.

Wearing a mask, in addition to being a requirement, was also an expression of care. It was one part of an integrated approach to caring for the whole-selves of people who had made the difficult decision to leave homes and families to come to NIH. They had made sacrifices in order to be a part of efforts to increase medical understanding and find new, lifesaving treatments.

Wearing a mask was an adjustment for me. It felt alien. It felt difficult. It made me worry that I wouldn’t be able to connect as well with the folks I was visiting, that they wouldn’t be able to read my facial expressions, that it created a barrier between us.

I didn’t like wearing a mask.

And of course, I did. I did because it was required, yes, but also because it was the caring thing to do, the loving thing to do, the thing that, though it felt like a barrier, was actually what facilitated the ability to meet the people whose well-being was entrusted to us exactly where they were. In this way, the mask and gown were “good boundaries,” rather than barriers, allowing beneficial connection and preventing harmful interaction.

I’ve been thinking about this experience of mask-wearing recently, in the midst of this pandemic and the politicization of mask-wearing in our country. (I thought this overview at Five Thirty Eight was helpful in cutting through some of this oddly polarized debate, and reminding us what we do and do not know about the efficacy of simple cloth face masks). And I’ve been trying to remember a few things:

While wearing a mask became routine while I was at NIH, for me it was a break from the norm. Especially at first, if felt weird, alien, and constricting.

Because I had to wear a mask, gown, and glove, those things were provided to me. They were available outside of every single room in which I would need to don them. If we require things, we need to supply them.

I was given specific training and guidance in how to take the mask and other protective equipment on and off, which may seem basic but in fact taught me many things I hadn’t instinctively known. If we require things, we have to teach them and learn them.

I wore a mask both because it was required for my job and also because it was helpfully connected, not just with ‘the rules,’ but with the provision of care

The mask wasn’t to protect me, but to protect others.

Leadership in the organization modeled mask wearing and other good hygiene practices, very intentionally avoiding any hint of a “do as I say, not as I do” mentality

At a recent vigil and march in Wilson. Photo by Drew Coleman of 24K Empire LLC.